Lazarus Resurrected

Prof. Jones

English 415

Toward a Digital Edition of the Towneley Lazarus Play

(Huntington MS HM 1, f129 - f131)

This essay is an attempt to expand upon a project that I began last year for Suzanne Gossett’s class on textual criticism. My original project’s goal was to produce a serviceable web-based edition of the Lazarus play found in the Towneley manuscript. The results were sketchy at best. The edition would only render properly in the most standards-compliant browsers, and my markup was nightmarish spaghetti code.1 I do not believe, however, that my initial project was in vain. The process of learning and successfully implementing new methodologies is arduous. Jerome McGann, lamenting “the degree of ignorance about information technology and its critical relevance to humanities education and scholarship,” relates similar sentiments:

I’ve spent almost 20 years studying this subject in the only way that gives a chance of mastering it. That is, by hands-on collaborative interdisciplinary work. By designing and building the tools and systems that alone will teach one what these tools are and what they might be, what they mean and what they might mean. You don’t learn a language by talking about it or reading books. You learn it by speaking it and writing it. There’s no other way. Anything less is just, well, theoretical. (“Culture and Technology” 3)

While I am still far from a master of the electronic edition, I remain intrigued both with the Towneley Lazarus and with the possibilities of the electronic edition. The remainder of this essay will explore that interest. First I shall articulate my initial goals for the project and my experience implementing those goals. Then I shall discuss the theoretical and practical implications of an electronic edition of the Towneley Lazarus.

“Com furth, lazare, and stande vs by”: Reflections on the First Stage

The Towneley Lazarus interested me for several reasons. I’ve always been fascinated by the idea of the eschaton. (What happens when or after we die? What is the end? Is there an end?) During the first half of the play, the characters are also concerned with death. The apostles fear for Jesus’ life as he plans to return to Judea; Jesus is concerned for the wellbeing of Lazarus; and Mary and Martha lament the death of their brother. Mary mourns that Jesus did not arrive sooner: “ffor it is now the iiii day gone / sen he Was laide vnder yonde stone” (83-84).2 According to John’s gospel account, the source for the play, Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead, and there is much rejoicing. The Towneley Lazarus, however, does not end happily. Lazarus himself addresses the other characters—as well as the audience. His words are grim, as he describes the torment of being devoured by worms and the likelihood of being abandoned by friends and family still on earth (103-236). His speech concludes the play and consists of over half of the play’s text.

It is remarkable that Lazarus is so concerned with sin, decomposition, and abandonment. According to Judeo-Christian tradition, he very well could have been with God, in the bosom of Abraham, or at least in a state of suspension. This tension is another aspect of the play that interests me. For it seems that Lazarus addresses concerns more appropriate for a late-medieval English audience. He does not believe in the efficacy of indulgences and he doubts the holiness of priests and other clerical orders; both of these concerns echo the “Lollard” heresy associated with John Wyclif and his followers and would resurface as the Reformation loomed. So the play’s cultural context intrigued me as well, especially in the moments when it conflicts with its source.

But these interests in themselves don’t seem to necessitate a digital edition of the play. The project, as I had conceived it to that point, would develop into a sort of “hyper-variorum” edition that would contain the play’s sources and analogues and its critical reception. My desire to trace the play’s social history stems from my infatuation with Bakhtinian theory, especially as articulated by his “Voloshinov” persona:

No cultural sign, once taken in and given meaning, remains in isolation: it becomes part of the unity of the verbally constituted consciousness. It is in the capacity of the consciousness to find verbal access to it. Thus, as it were, spreading ripples of verbal responses and resonances from around each and every ideological sign. Every ideological refraction of existence in process of generation, no matter what the nature of its significant material, is accompanied by ideological refraction in word as an obligatory concomitant phenomenon. (52)

That is, signs signify past, present, and future signifieds at the same time. In terms of hypertext, this process of instantaneous and perpetual meaning resembles Theodor Nelson’s “evolutionary file structure” (137). Links among data perpetually grow. A print edition can accommodate such growth, but only slowly and then only if editor and publisher agree to revise an edition or publish supplements. In an idealized form of hypertext, such concerns are moot: space is unlimited and the edition could be publicly revised, not the intellectual property of only a few.

Any text, however, can be conceived in those terms. For cultural knowledge always grows, if only subconsciously. Moreover, all texts are social: they “are saturated with prior interpretations, prior understandings” (Vorhes par. 8).3 Fortunately for my project, the Towneley Lazarus poses some unique challenges, which I shall now address.

The Towneley Lazarus does not appear in the manuscript at the appropriate time, at least according to John’s narrative. The scriptural account places the raising of Lazarus immediately before the passion narrative. The Towneley manuscript places these events not only after Christ’s crucifixion, harrowing of Hell, and resurrection, but also after the play concerning the last judgment. “This placement does not appear to be an accident: the text is bound with the judgment play (not a later paste-in, e.g.), and the usually careful scribe does not account for this error” (Vorhes par. 6). The problem is compounded because the Towneley manuscript is the only text that contains this play cycle.4 The placement of Lazarus thus raises troubling questions. What meaning does the text convey if it appears after the last judgment? Is it about a very literal resurrection of the body? If the play occurs after the last judgment, why does Lazarus, who is supposedly faithful to Christ, experience a sort of hell in death? Why is there even death any more?

In my germinal electronic edition, I wanted to play with some limited manuscript possibilities, the kind one can’t physically perform without destroying book or manuscript. I provided three ways to read my edition of Lazarus: in isolation, in an approximation of its manuscript context, and where it would go according to John’s narrative. By positioning the play in these ways, I imagined myself practicing a limited kind of “deformance,” Jerome McGann’s articulation of crtical methodologies that attempt to expose a text’s “possibilities of meaning,” through the processes of reordering, isolating, altering, and adding text (Radiant Textuality 105-35).

Despite the unpredictability that deformace implies, I had hoped to find a stable interpretation as a result. Instead, I met no certainty. According to the Biblical narrative in the Towneley plays, Lazarus would follow the play of John the Baptist. The Baptist concludes that play, which I reproduce here from the recent Cawley and Stevens edition (226):

Syrs, forsake youre wykydnes,

Pryde, envy, slowth, wrath, and lechery.

Here Gods seruice, more and lesse;

Pleas God with prayng, thus red I;

Bewar when deth comys with dystres,

So that ye dy not sodanlyDeth sparis none that lyf has borne;

Therfor thynk on what I you say:

Beseche youre God, both euen and morne,

You for to saue from syn that day.

Thynk how in batpym ye ar sworne

To be Godys seruandys withoutten nay.

Let neuer his luf from you be lorne;

God bryng you to his blys for ay! Amen. (275-88)

Here John exhorts his listeners to repent before they are out of time, lest death surprise them. His closing speech anticipates the despairing warnings from the risen Lazarus, who believed that he himself was out of time. Thus he almost immediately affirms John the Baptist’s theology of repentance and contrition. But Lazarus can also report on the doom that the bad souls face in the play of the last judgment. In either context, Lazarus follows on plays that at least conclude by articulating punishment for unrepentant sinners. While my deformative acts did not create a singular interpretation, they certainly allowed for a richer understanding of the play.

“Amende the man Whils thou may”: Concerns about the Future

In my overt gestures toward a deformative interpretation, I kept it simple. Others have pushed this idea to extremes.5 As of yet, I do not have the technical expertise to accomplish such digital wonders. But my initial edition is more deformative than I realized at the time. I had begun to encode the edition with previous critical interpretations and to embed glossarial references for particularly difficult words. Such work, John Lavagnino observes, is commonplace:

Scholarly editions [of any kind] involve the creation of new writing as well as work on existing texts: editions usually include introductions and commentary in some form, and may extend to such things as analytical essays, catalogues of sources or witnesses, and bibliographies. (par. 2)

These accretions are more apparent in the encoding of a digital edition (or, for that matter, the encoding of this essay). Consider my HTML for the play’s opening speech:

<!— Jesus —>

<p class="newspeech">

<div class="note"><acronym title="EP (1-6): “Jesus proposes to go to Bethany to visit Lazarus, who is ill."“>note</acronym></div>

<span class="spkr"><dfn title="Jesus">Ih<span class="abr">esu</span>s</dfn>.</span>

Commes now <dfn title="brothers">brethere</dfn> and go With me:

</p>

<p>We Will pas <dfn title="forth">furth</dfn> <dfn title="into">untill</dfn> <dfn title="Judea">Iude</dfn>.</p>

<div class="note"><acronym title="3 & 4. These lines are reversed in the MS. The scribe added corrections (CS): 3 is preceded by “B/.” 4 is preceded by “A/.”">note</acronym></div>

<p>To <dfn title="Bethany">betany</dfn> will we <dfn title="travel">Weynde</dfn>,</p>

<p>To vysit <dfn title="Lazarus">lazare</dfn>, that is our freynde.</p>

<div class="note">5</div>

<p>Gladly I <dfn title="wish">wold</dfn> we with hym speke;</p>

<p>I tell you <dfn title="truthfully">sothely</dfn> he is <dfn title="sick, ill">seke</dfn>.</p>

In order to render the material, I had to use an extensive style sheet; and I abused certain tags, such as <abbr>, in order to embed textual notes. (This latter technique seemed handy until I realized that different user agents handle title elements in different ways, frequently truncating the contents.)

If I remove all of my corruptions of HTML, my markup still operates as a deformation of the text. In following Peter Baker’s recommendations for how to encode a text,6 I have an opening speech whose semantic meaning remains obscured:

<p><!— Jesus —>

<span class="line"><span class="lnnum hide">1</span><cite class="spkr">Ihesus.</cite> Commes now brethere and go With me:</span>

<span class="line"><span class="lnnum hide">2</span>We Will pas furth untill Iude.</span>

<span class="line"><span class="lnnum hide">3</span>To betany will we Weynde,<!— line 4 in MS —></span>

<span class="line"><span class="lnnum hide">4</span>To vysit lazare, that is our freynde.<!— line 3 in MS —></span>

<span class="line"><span class="lnnum">5</span>Gladly I wold we with hym speke;</span>

<span class="line"><span class="lnnum hide">6</span>I tell you sothely he is seke.</span>

</p>

Indeed, not until one views the rendered text does that additional obscurity fall away. I suspect this has partly to do with the visual lack of obvious structural meaning, aside from such commonplaces as “poetic line” and “speaker.” Moreover, the marked-up text is still obscured. For the web browser, text parser, or whatever interface operates as a mediator between editor and reader. The HTML encoding is still present. The user agent just chooses to render it differently.

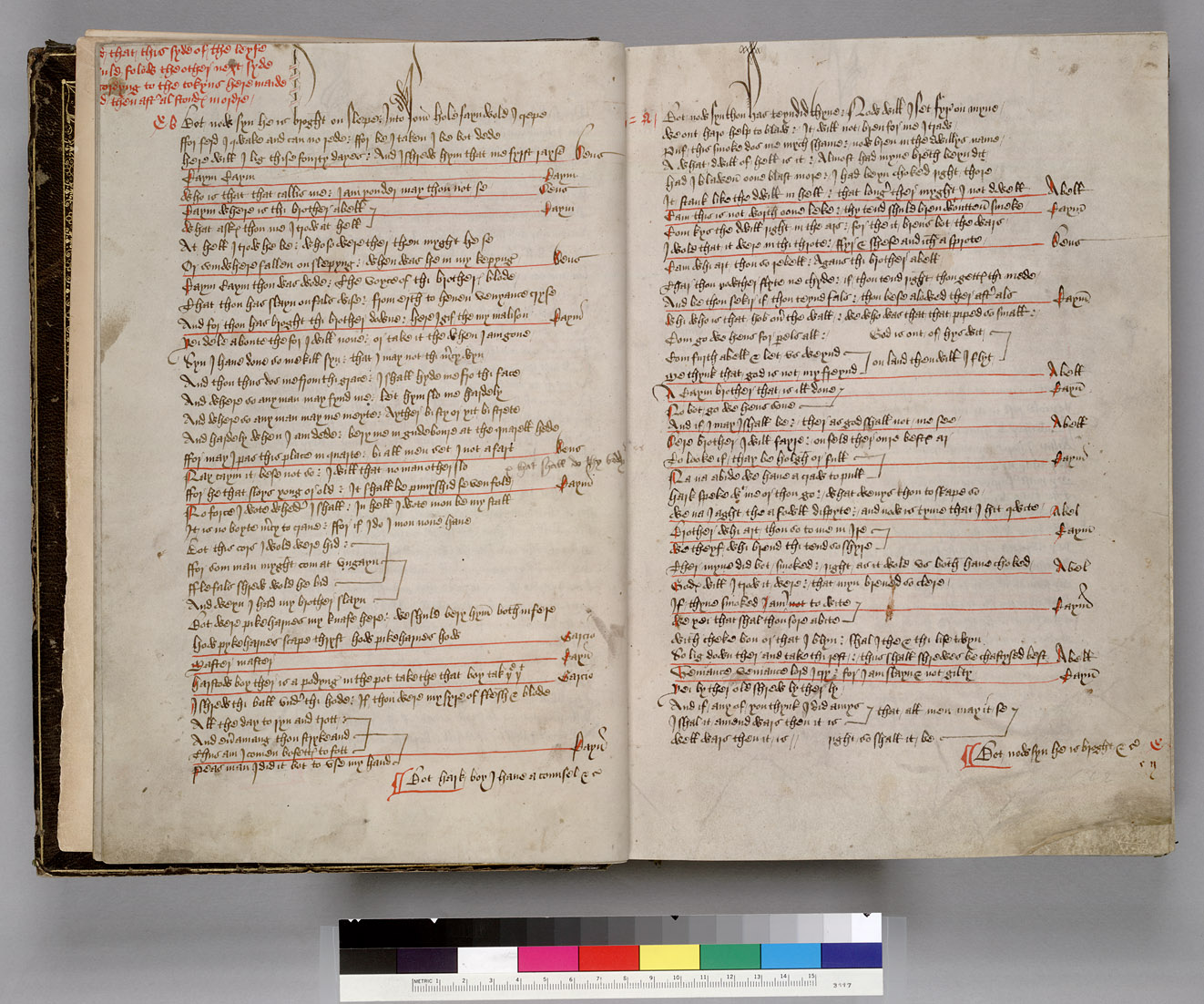

Figure 1: f1.

The beginning of the Towneley MS. Note the “vine stem initial capital” & the “Towneley Press mark.” 7

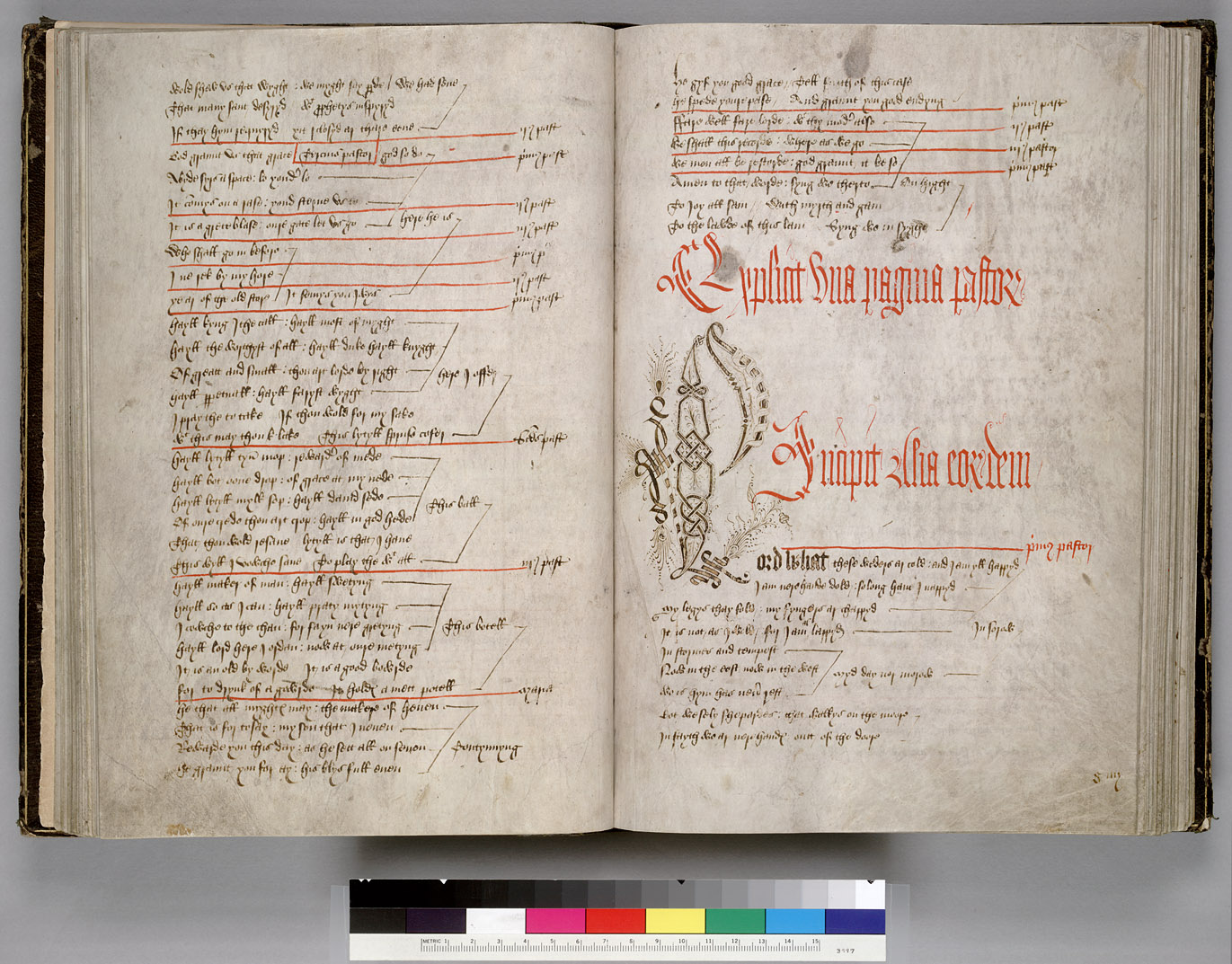

Figure 3: f37v-38.

“Beginning of 2nd Shepherd’s Play, quire & leaf signatures, textura display script title, & strapwork calligraphic initials.”

More important to the “presentational” edtion, however, is what is absent from the rendered screen. Note in the code above the instances opened with <!— and closed with —>. The typical HTML rendering engine ignores these as comments. In the first instance in the example, such a visual omission is unproblematic: I used the comment tags to mark when the speech began and who spoke it, for ease in working within a text editor. But remaining two comments are important not only to the edition, but also to the manuscript. In the manuscript, lines three and four are switched. In the left margin of the page, the scribe as written “B/” before the third manuscript line, and “A/” before the fourth. The signification is clear, that the scribe has written these lines out of order. If I were working on a print edition, I would probably make note of these marginalia in a lemma at the foot of the page. What does one do when there is no foot?

XML offers greater flexibility in this case. Moreover, organizations like the Text Encoding Initiative Consortium have been developing standards, or “best practices,” for the encoding of digital editions. TEI markup, following the XML standards on which it is based, is structural—as opposed to HTML, which is primarily presentational. A brief perusal of TEI documentation reveals that TEI-based documents can be almost as flexible as an editor desires. Moreover, it is possible to employ software that can transform XML according to user specifications. An XML-encoded Towneley manuscript, for example, would allow an on-the-fly deformation of my triply-presented Lazarus without “destroying” the transcription.

Kevin Kiernan seems especially excited by the possibility of encoding manuscript images via TEI:

While some people continue to think of electronic texts as exclusive of images, the fact is that digital images of manuscripts are electronic texts, as well. The most compelling scholarly editions of the future will make full use of markup schemes such as XML (or its TEI manifestation), but not without extensive integration of images. (par. 6)

Such a move would be especially useful in my own edition of the Towneley manuscript. For example, TEI would allow me to encode Figure 1 in such a way that I acknowledge its “vine stem initial capital” or even the damage that the page has sustained. At the same time, however, I am ambivalent toward TEI encoding for manuscript. For TEI is a rigidly-structured markup language. How does one account for the scribe’s rubricated marginalia in Figure 2, or handle the incredibly elaborate black lines that denote matching end rhyme so prevalent in Figure 3?

The link between XML-described transcription and the transcription’s related images is still in its infancy. Perhaps later iterations of TEI (or some other markup language) will allow for greater structural flexibility. Matthew Kirschenbaum suggests that we are not too far from directly encoding digital images:

vector imaging enfolds graphical representations within textual data structures; the Scalable Vector Graphics (SVG) standard, an XML-based spec which currently has the status of a Recommendation to the World Wide Web Consortium, would enable visual data to be expressed as machine-readable text. Likewise, […] the scalable and modular properties of vector formats lend themselves extremely well to integration with databases and encoded texts. But the point I most want to emphasize here is that the greatest significance of vector graphics in the humanities, is that they will, I believe, force us to confront head-on our dependence upon documentary forms of knowledge, a guilty habit which we have rushed to indulge in our digital embrace of elaborate archival shrines to the documentary ideal, loaded with 24-bit color high-resolution raster representations. (4)

Kirschenbaum’s challenging traditional editorial habits is especially apt in the field of medieval studies. John Dagenais has recognized the medievalist habit to relegate medieval manuscripts to the tired status of ancient artifact:

Our reasons for using the term ‘medieval page,’ of course, are that these subjects were produced in the Middle Ages, originate in the Middle Ages, and are therefore ‘medieval.’ We have chosen to privilege their ‘origins’ over their very real ‘presence’ to us. We have marked them within the institutionalized spaces of the library and of academic discourse. In a move typical to all colonizations, we have denied the coevalness of the manuscript page. (67)

Kiernan has also recognized this academic problem, but he suggests a way out of the postmodern conundrum, the problem with no solution:

One of the few certainties we have about authorial intentions from the Middle Ages is that neither authors nor scribes (who may sometimes be the same person) ever intended their work for print or PC. These writers none the less supplied their texts with meaningful text encoding, which modern editors, because of the limitations of print and the different conventions of modern literacy, have routinely ignored or unavoidably misrepresented in modern editions. [. . .]

Changes from script to print should in fact be viewed as radical modernizing translations of source documents, not the usual stuff of scholarly editions. It is comparable to an editor of a modern text removing all punctuation, dividing words into syllables, providing ancient spellings, and displaying poetry without lineation. Before the advent of digital technology, editors of medieval texts were virtually forced to make these translations of their sources, if they wanted modern readers to understand the texts. (pars. 1, 4)

For Kiernan, who works primarily with Anglo-Saxon texts, the destructive potential of print is obvious. Old English manuscripts are written using different letterforms (and sometimes runes). They do not obviously distinguish between prose and poetry—or at least how we expect them to appear. Frequently the medieval manuscript defies our expectations. The further development of the digital edition, then, opens up new horizons, not only for the scholar, but also for the student. For grayscale facsimile editions, extremely costly in print, can be supplanted by color facsimile editions encoded in digital media. The latter allows not only for access to a more aesthetically pleasing image of the manuscript, but also the possibility of encoding that image so that it is more than merely image.

The prospects for digital scholarly editions are exciting. Despite my best efforts, however, to engage with digital editorial theory and to work through an edition of my own, I still feel as if I’m at surface of things. Little anxieties haunt my mind. How can one “encode” an image with information? How can one access that information? If the digital edition demands a database-driven backend, what does that database model do to my conception of text? I find myself returning to the wisdom of Jerome McGann, with which I began this essay, this meandering thought-pattern, this quest: “You don’t learn a language by talking about it or reading books. You learn it by speaking it and writing it. There’s no other way.” It’s time, then, to continue working.

Notes

See the “spaghetti code” for yourself by following this link and viewing the source code in your browser. It probably doesn’t help that the HTML isn’t valid.

[ back ]

Unless otherwise noted, all quotations from the play are from a “cleaned-up” version of my edition, which I will discuss in due time.

[ back ]

Please forgive my own egotism, since I probably could have found something similar from Bakhtin or McGann. It’s exciting stuff to quote oneself!

[ back ]

Cawley and Stevens, in their edition, provide a judicious account of the critical debate that has resulted from this manuscript problem (646-50). I should note, however, that I disagree with their conclusion, though I have yet to figure out an adequate way to articulate my disagreement.

[ back ]

See, for example, the Flash-based “create your own Bayeux Tapestry” by Karnebogen et Ivngblvth.

[ back ]

I should note that Baker addresses the issues inherent table-based design, a problem different from my own.

[ back ]

Clicking on the image will open the full-size version. (All image descriptions are adapted or quoted from the Berkeley Digital Scriptorium. The images themselves are property the Huntington Library.)

[ back ]

Bibliography

- Baker, Peter. “Web Standards for Medievalists.” International Congress on Medieval Studies. Kalamazoo, MI. 7 May 2004.

- Burnard, Lou, Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe, and John Unsworth, eds. Electronic Textual Editing. Text Encoding Initiative Consortium. 27 Nov. 2004. 29 Apr. 2005. [ link ]

- Cawley, A. C., and Martin Stevens, eds. The Towneley Manuscript: A Facsimile of Huntinton MSHM 1. Leeds Texts and Monographs. Ilkley, Yorkshire, UK: Scolar, 1976.

- Cawley, A. C., and Martin Stevens, eds. The Towneley Plays. 2 vols. EETSSS 13. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1994.

- Dagenais, John. “Decolonizing the Medieval Page.” The Future of the Page. Ed. Peter Stoicheff and Andrew Taylor. Studies in Book and Print Culture. Gen. ed. Leslie Howsam. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2004. 37-70.

- Karnebogen et Ivngblvth. “Historic Tale Constrvction Cit.” 2003. 12 May 2005. [ link ]

- Kiernan, Kevin. “Digital Facsimiles in Editing.” Burnard, O’Brien O’Keefe, and Unsworth.

- Kirschenbaum, Matthew G. “Vector Futures: New Paradigms for Imag(in)ing the Humanities.” 2002. 1 Mar. 2005. [ link ]

- Lavagnino, John. “When Not to Use TEI.” Burnard, O’Brien O’Keefe, and Unsworth.

- McGann, Jerome. “Culture and Technology: The Way We Live Now, What Is To Be Done?” 23 Apr. 2004. 2 May 2005. [ link ]

- McGann, Jerome. Radiant Textuality: Literature after the World Wide Web. New York: Palgrave, 2001.

- Nelson, Theodor H. “A File Structure for the Complex, the Changing, and the Indeterminate.” 1965. The New Media Reader Ed. Noah Wardrip-Fruin and Nick Montfort. Cambridge, MA: MIT P, 2003. 134-45.

- Voloshinov, V. N.“From Marxism and the Philosophy of Language.” 1929. Trans. L. Matejka and I. R. Titunik. The Bakhtin Reader: Selected Writings of Bakhtin, Medvedev, and Voloshinov. Ed. Pam Morris. London: Arnold, 1994. 50-61.

- Vorhes, Erik. “An Explanation.” Electronic Lazarus Project. 15 Apr. 2004. 23 Apr. 2005.